Recently, I talked to a couple of designers that I have worked with previously about an upcoming potential job. They told me that they wouldn’t do it “on spec” which, I have to admit, took me back a bit because I didn’t expect them to do the work for free.

In theatre, designers, in my experience, are hired based on their reputation, portfolio, and so forth. It is common for certain directors to request a certain designer based on the show and a previously existing relationship. Designers, at least professionally, are not expected to work for free. Once hired, they are expected to make the design work for the director.

Working in a commercial scene shop, some clients think of design the same way that I do – that they hire us based on reputation, relationship and portfolio, and we work together to make a design that everyone is happy about. Technically, we could do a design and not do the fabrication, though that doesn’t happen often. Also, I suppose that if a design wasn’t going well, they could pay for services to date and move on, though that doesn’t really happen either. However, there are a variety of customers, who work in other industries where they do expect us to design and/or sample and develop ideas for free. There is really quite a debate about this practice & about how it can be bad for the industry in general. It reminds me of the debate I heard when I was younger about how the theatre industry underpays in general, but especially for interns because it’s a learning experience and besides – you are doing what you love. I have to admit that my early days in theatre were in small places that economically took advantage of me, but I did gain a lot of experience. On the other hand, I have seen others take a much different career trajectory.

The other challenge with design and prototype / sample proposals is quantifying what they entail. If it is unlimited, a client could take advantage wanting endless samples, drawings, revisions, and so forth. If you price based on the assumption that something like that will happen and try to allow for time and materials, your cost will be too high. If you assume the best case scenario, but don’t put any limits into the contract then you may lose money on the work. I have some people do a time/materials proposal, but generally people want to have a final price in mind for the budget. If you do a proposal that specifies a particular process and amount of revisions etc, and allows for additional charges – it allows everything to be very clear to both parties, and minimizes risk to the artist, but I have seen clients shy away-to a certain degree once they pay for design they want it to be finalized without additional charges and have a hard time recognizing how their actions and request increase costs.

While I don’t really have answers, I think that ultimately it is about a relationship.

David Airey has a blog that talks about spec work. He also has many good resources for designers.

Thursday, March 27, 2014

Tuesday, March 25, 2014

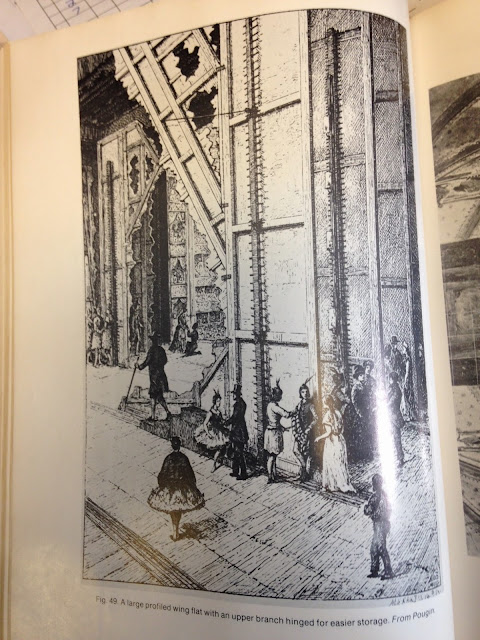

New Stage Machinery in 1873

In an article “the New Theatre” published in the New York Times on 1873 (not to be confused with Claude Hagen’s new theatre that occurs 40 years “ish” later) also reference James Schonberg as contributing to designing the stage. The building is being done by architect, Frederick Draper. The proscenium “will be of original form and construction, the plans for it having been designed by Mr. Dion Boucicault, and will be so formed as to act as a sounding board.” The stage is described as having many improvements by Boucicault and Schonberg. The stage is described as 40 squares, each 3’ which can be raised and lowered. These could also be used to create steps. This article describes a patent by Schonberg for supporting and setting the scenery, but also describes traditional scenery (defining it by two types, English and French). The article describes French Stage shifting equipment as a truck beneath the stage with a ladder / frame that the scenery is mounted to. (Pictures below are from French Theatrical Production Nineteenth Century by J P Moynet). The article discusses advantages and disadvantages of this system. They describe the English system as having the scenery supported from above, by “grooves” or “parallel fillets”. This technique is said to be faster than the French system and able to be done in front of the audience. Disadvantages are that everything is square and that grooves must be masked. It also talks about stage screws and braces; obviously we have inherited many of these practices despite European theatrical influences. The article names Mr Flechter and the London Lyceum as advancing a system blending the techniques for shifting scenery, also including Boucicault and Schonberg. The new Lyceum Theatre (in NY) would be built with mechanisms described within the article (too lengthy to quote but freely available on the NY Times Archives Website).

In “Mr. Fechter’s Theatre”, published in the New York Times Jan 20, 1873, we see a continuation of the description of the theatre. It has a very elaborate account of the building itself. Included are items that involve fire safety such as doors that swing in both directions. The theatre was outfitted with gas lighting (that could change color and strength). The stage itself moved as well. The theatre includes a second “sounding-board” (proscenium) which moves upstage – downstage by way of stage machinery. The scenery is lifted from traps “upon what are termed parallel boats, are then attached to the stage, which, with the scenery upon it, can be moved completely out of sight of the audience.” Credit to the system was given to James Schonberg who was a stage manager at the Wallack’s Theatre, and the article states that he patented the system. W. Lester, a machinist, built the system. Absent from this account is Dion Boucicault’s contributions. Under the stage, the area is described as “a perfect labyrinth of cranks, wheels, parallel boats and other mysteries, all worked by hand”. The workshops are also under the stage, while the scenic painter’s gallery is behind the stage, in use by painters Hosford and Laran.

Further New York Times articles indicate that James Schonberg was also a playwright.

His patent can be seen online as well: US 123735

As a side note, I have come across many references to technicians referred to bay their last name only (though very politely). This makes tracing these names more difficult, if not impossible, at least with the fairly searches that I am doing within this research. I assume that they have shorted the names to save space, or because they considered the first names unimportant and not that there was an assumption that they were so well known that first names were not needed. I say this because many names that I am more familiar with are fully spelled out.

In “Mr. Fechter’s Theatre”, published in the New York Times Jan 20, 1873, we see a continuation of the description of the theatre. It has a very elaborate account of the building itself. Included are items that involve fire safety such as doors that swing in both directions. The theatre was outfitted with gas lighting (that could change color and strength). The stage itself moved as well. The theatre includes a second “sounding-board” (proscenium) which moves upstage – downstage by way of stage machinery. The scenery is lifted from traps “upon what are termed parallel boats, are then attached to the stage, which, with the scenery upon it, can be moved completely out of sight of the audience.” Credit to the system was given to James Schonberg who was a stage manager at the Wallack’s Theatre, and the article states that he patented the system. W. Lester, a machinist, built the system. Absent from this account is Dion Boucicault’s contributions. Under the stage, the area is described as “a perfect labyrinth of cranks, wheels, parallel boats and other mysteries, all worked by hand”. The workshops are also under the stage, while the scenic painter’s gallery is behind the stage, in use by painters Hosford and Laran.

Further New York Times articles indicate that James Schonberg was also a playwright.

His patent can be seen online as well: US 123735

As a side note, I have come across many references to technicians referred to bay their last name only (though very politely). This makes tracing these names more difficult, if not impossible, at least with the fairly searches that I am doing within this research. I assume that they have shorted the names to save space, or because they considered the first names unimportant and not that there was an assumption that they were so well known that first names were not needed. I say this because many names that I am more familiar with are fully spelled out.

Monday, March 24, 2014

Entertainment Design & Technology Blog

Jeromy Hopgood writes a blog called Entertainment Design & Technology. It is fairly new and has limited content, but the posts are interesting. I linked specifically to an entry about doing visual research.

Sunday, March 23, 2014

Stage Carpenter for Herne, the Hunter

I was reading an article from the New York Times Archive called “Broadway Theatre” published on Feb. 19. 1856 about a show called “Herne, the Hunter”. Evidently the show did not go well since the author states that “neither the scenery nor the machinery worked well. … Large demands are made on the stage carpenter, and it will be one or two nights before everything can be expected to work with exact precision.” Later though, the author claims that the scenery is good, but that it needs to be better lit.

This predates the first version of IATSE, which was the Theatrical Workman’s Council (started in 1863). It also seems to predate commercial scene shops, most of which seem to have started opening around 1890, though I am sure that there were builders operating before that out of a small shop, just as there are individuals today doing the same.

We have Stage Carpenters today of course; they typically help during load in, and run and maintain a show. If it’s a tour, the carpenter would likely be a Show Carpenter or perhaps a Technical Supervisor. Depending on the venue, a theatre may have an IATSE crew, and the “head” would be the steward. This person generally manages crew – but doesn’t usually handle dealings with the client, so it’s a tricky separation.

This predates the first version of IATSE, which was the Theatrical Workman’s Council (started in 1863). It also seems to predate commercial scene shops, most of which seem to have started opening around 1890, though I am sure that there were builders operating before that out of a small shop, just as there are individuals today doing the same.

We have Stage Carpenters today of course; they typically help during load in, and run and maintain a show. If it’s a tour, the carpenter would likely be a Show Carpenter or perhaps a Technical Supervisor. Depending on the venue, a theatre may have an IATSE crew, and the “head” would be the steward. This person generally manages crew – but doesn’t usually handle dealings with the client, so it’s a tricky separation.

Tuesday, March 18, 2014

Lab Theatre

Traditionally, when talking about a lab theatre, one might think about a black box space. Now however, we can test some technical ideas out in a model theatre, allowing experimentation before time is limited during tech week.

Yeagerlabs includes scaled softgoods and lighting packages.

Lightbox also has a scaled model of a theatre. I have seen this in use at USITT, but have also seen it in development at Syracuse University. This website seems to be out of date, so I am not sure if they are still in existence or not.

Both of these instruments seem to be primarily effective for lighting experimentation – still leaving room for future development for scenic automation experimentation.

Yeagerlabs includes scaled softgoods and lighting packages.

Lightbox also has a scaled model of a theatre. I have seen this in use at USITT, but have also seen it in development at Syracuse University. This website seems to be out of date, so I am not sure if they are still in existence or not.

Both of these instruments seem to be primarily effective for lighting experimentation – still leaving room for future development for scenic automation experimentation.

Tuesday, March 11, 2014

Carl Lautenschlager, Technical Director.

The earliest mention of a “Technical Director” within the New York Times is in an article titled “Conried Tells his Plans” published on May 14, 1903. Within the article Conreid (a producer) announces that Carl Lautenschlager will REMAIN with him as TD for work at the Metropolitan Opera House. The article also describes that a new lighting system, counterweight system, stage floor, and costumes will be purchased and installed, and a revolving stage is to be added a year later. These improvements are probably for “Parsifal”.

In a December 20, 1903 article in the New York Times, called “”Parsival,” The Music Drama” outlines the story. It announces the upcoming opening of the show. The article lists Lautenschlager as “Technical Director (in charge of all mechanical and electrical effects)” as part of the cast list. Further, the article indicates that Lautenschlager has rebuilt the stage and “devised” lighting, and claims that he “has no rival in his own field in Europe.” It is also interesting to note that “including the electricians, property men, stage hands, supernumeraries, and choruses, nearly 300 persons” are involved. While we cannot be certain how many of these people filled a technical role versus being on the stage, it does suggest a vastness of scale to the production.

Several days later, the New York Times, on December 25, 1903, claims “”Parsifal” A Triumph”. This article indicates that “The chief masters of stage craft and of scenic manipulation had been summoned from Germany to superintend and co-ordinate the material factors.” The article also lists Lautenschlager as part of the cast list.

Henry Edward Krehbiel offers information to the end of Carl’s tenure in the USA. In Chapters of Opera, published in 1911, Carl is mentioned as “stage mechanican, or technical director” and it is claimed that despite doing notable work in “Parsifal” he was “hampered by the prevailing conditions” and returned after a year to Germany.

Carl Lautenschlage also is mentioned within The Election, Volume 34, on March 29, 1895. Here he is described as a “great Bavarian stage machinist”, and is working on London on a new ballet. He is also credited as being “well known in theatrical circles as electrician to the Court Theatre of Bavaria, and his efforts to introduce the use of electricity in connection with the machinery of the stage have been crowned with considerable success.” It would seem as though this would indicate that he is the father of theatre automation as well as perhaps America’s for Technical Director. It is clear from what I am reading about Lautenschlage, Hagen, and others that they were generally machinists, involved in lighting, as well as involved with installing large scale stage mechanics for the stage, not just for an individual production.

Revolving Architecture: A History of Buildings that Rotate, Swivel, and Pivot by Chad Randi, states that the first patent for a rotating stage was in 1883 by Charles Needham, but was not built. The Fifth Avenue Theatre evidently had a master machinest that also proposed a turntable. In Germany, Karl Lautensschlager was working at the Mucich Court and Residence Theatre and installed, in 1896, the first permanent rotating stage in the Western part of the globe. He was also looking at lifts and traps, similar to what Claude Hagen would later install in the New Theatre in NY. Further, Carl is also credited with installing 4 of these in major cities throughout Europe. This author claims that the first rotating stage in America was at Ye Liberty Playhouse in Oakland, Ca in 1903. Harry Bishop is listed as the “manager”, who may have been influenced by Japanese Kabuki stages. It is clear from the description that this was manually operated by stagehands. That Lautenschlager was first is also supported by The Japanese Theatre: From Shamanistic Ritual to Contemporary Pluralism by Benito Ortolani.

He is also mentioned in Theatre Technology by George Izenour. Izenour is about to produce quite a bit about his background. Carl was born Arpil 11, 1843. After he father died, he mother remarried to a man that was a stage inspector. As he started working he originally studied under Carl Brandt, eventually moving to Munich and working there for 22 years. While there, he was sent to Paris to study an electrical exhibition there. Upon his return to Munich he installed electric lighting. Working with Jocza Savits they reinvented the way Shakespear was performed. He is also listed as working with Ernst Possart for the development of the rotating stage. Izenour states that he retired in 1902 (though we know that he came to the US), and that he died on June 30, 1906. It seems as though once he went back to Germany after his American tenure, he did not return to the stage.

He is also mentioned in Wagner Nights: An American History by Joseph Horowitz, Richard Struss: A Chronical of the Early Years, 1864-1898 by Will Schuh (credited with installing a revolving stage in 1896 in the Residenztheatre), Richard Wagner and His World by Thomas S. Grey (a photo is available of Carl here), The Dramatic Touch of Difference: Theatre, Own and Foreign edited by Erika Fischer-Lichte, Josephine Riley, Michael Gissensehrer (though this is a fleeting reference), The Development of methods for Flying Scenery on the English Stage, 1800-1960 by Susan Stockbridge, a supplement written by Lautenschlager in Scientific American Supplement, no 1541 (July 15, 1905), Early Uses of Electricity for the Theatre:1880-1900 by Walter Kenneth Waters Jr.

Wikipedia also offers the following bibliography:

The American Architect and Building News. Volume 53. Boston: American. Architect and Building News Co, 1896.

Ackermann, Friedrich Adolf. The Oberammergau Passion Play, 1890. Fifth Edition. Munich: Friedrich Adolf Ackermann, 1890.

Fuerst, Walter René and Hume, Samuel J. Twentieth-Century Stage Decoration. Volume 1. New York: Dover Publications, 1967.

Hoffer, Charles. Music Listening Today. Fourth Edition. Boston: Schirmer Cengage Learning, 2009.

Izenour, George C. Theater Technology. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

MacGowan, Kenneth. The Theatre of Tomorrow. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1921. Print.

Ortolano, Benito. The Japanese theatre: from shamanistic ritual to contemporary pluralism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Randl, Chad. Revolving architecture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008. Print.

Sachs, Edwin. Modern Theatre Stages. New York: Engineering, 1897. Print.

Vermette, Margaret. The Musical World of Boublil and Schönberg: The Creators of Les Misérables, Miss Saigon, Martin *Guerre, and The Pirate Queen. New York: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2006.

Williams, Simon. Shakespeare on the German stage: 1586–1914. Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

WPG, . The Revolving Stage at the Munich Royal Residential and Court Theatre. New York: American Architect and Architecture, 1896. Print.

It also seems that more would be available if I was able to do additional research in German.

In a December 20, 1903 article in the New York Times, called “”Parsival,” The Music Drama” outlines the story. It announces the upcoming opening of the show. The article lists Lautenschlager as “Technical Director (in charge of all mechanical and electrical effects)” as part of the cast list. Further, the article indicates that Lautenschlager has rebuilt the stage and “devised” lighting, and claims that he “has no rival in his own field in Europe.” It is also interesting to note that “including the electricians, property men, stage hands, supernumeraries, and choruses, nearly 300 persons” are involved. While we cannot be certain how many of these people filled a technical role versus being on the stage, it does suggest a vastness of scale to the production.

Several days later, the New York Times, on December 25, 1903, claims “”Parsifal” A Triumph”. This article indicates that “The chief masters of stage craft and of scenic manipulation had been summoned from Germany to superintend and co-ordinate the material factors.” The article also lists Lautenschlager as part of the cast list.

Henry Edward Krehbiel offers information to the end of Carl’s tenure in the USA. In Chapters of Opera, published in 1911, Carl is mentioned as “stage mechanican, or technical director” and it is claimed that despite doing notable work in “Parsifal” he was “hampered by the prevailing conditions” and returned after a year to Germany.

Carl Lautenschlage also is mentioned within The Election, Volume 34, on March 29, 1895. Here he is described as a “great Bavarian stage machinist”, and is working on London on a new ballet. He is also credited as being “well known in theatrical circles as electrician to the Court Theatre of Bavaria, and his efforts to introduce the use of electricity in connection with the machinery of the stage have been crowned with considerable success.” It would seem as though this would indicate that he is the father of theatre automation as well as perhaps America’s for Technical Director. It is clear from what I am reading about Lautenschlage, Hagen, and others that they were generally machinists, involved in lighting, as well as involved with installing large scale stage mechanics for the stage, not just for an individual production.

Revolving Architecture: A History of Buildings that Rotate, Swivel, and Pivot by Chad Randi, states that the first patent for a rotating stage was in 1883 by Charles Needham, but was not built. The Fifth Avenue Theatre evidently had a master machinest that also proposed a turntable. In Germany, Karl Lautensschlager was working at the Mucich Court and Residence Theatre and installed, in 1896, the first permanent rotating stage in the Western part of the globe. He was also looking at lifts and traps, similar to what Claude Hagen would later install in the New Theatre in NY. Further, Carl is also credited with installing 4 of these in major cities throughout Europe. This author claims that the first rotating stage in America was at Ye Liberty Playhouse in Oakland, Ca in 1903. Harry Bishop is listed as the “manager”, who may have been influenced by Japanese Kabuki stages. It is clear from the description that this was manually operated by stagehands. That Lautenschlager was first is also supported by The Japanese Theatre: From Shamanistic Ritual to Contemporary Pluralism by Benito Ortolani.

He is also mentioned in Theatre Technology by George Izenour. Izenour is about to produce quite a bit about his background. Carl was born Arpil 11, 1843. After he father died, he mother remarried to a man that was a stage inspector. As he started working he originally studied under Carl Brandt, eventually moving to Munich and working there for 22 years. While there, he was sent to Paris to study an electrical exhibition there. Upon his return to Munich he installed electric lighting. Working with Jocza Savits they reinvented the way Shakespear was performed. He is also listed as working with Ernst Possart for the development of the rotating stage. Izenour states that he retired in 1902 (though we know that he came to the US), and that he died on June 30, 1906. It seems as though once he went back to Germany after his American tenure, he did not return to the stage.

He is also mentioned in Wagner Nights: An American History by Joseph Horowitz, Richard Struss: A Chronical of the Early Years, 1864-1898 by Will Schuh (credited with installing a revolving stage in 1896 in the Residenztheatre), Richard Wagner and His World by Thomas S. Grey (a photo is available of Carl here), The Dramatic Touch of Difference: Theatre, Own and Foreign edited by Erika Fischer-Lichte, Josephine Riley, Michael Gissensehrer (though this is a fleeting reference), The Development of methods for Flying Scenery on the English Stage, 1800-1960 by Susan Stockbridge, a supplement written by Lautenschlager in Scientific American Supplement, no 1541 (July 15, 1905), Early Uses of Electricity for the Theatre:1880-1900 by Walter Kenneth Waters Jr.

Wikipedia also offers the following bibliography:

The American Architect and Building News. Volume 53. Boston: American. Architect and Building News Co, 1896.

Ackermann, Friedrich Adolf. The Oberammergau Passion Play, 1890. Fifth Edition. Munich: Friedrich Adolf Ackermann, 1890.

Fuerst, Walter René and Hume, Samuel J. Twentieth-Century Stage Decoration. Volume 1. New York: Dover Publications, 1967.

Hoffer, Charles. Music Listening Today. Fourth Edition. Boston: Schirmer Cengage Learning, 2009.

Izenour, George C. Theater Technology. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

MacGowan, Kenneth. The Theatre of Tomorrow. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1921. Print.

Ortolano, Benito. The Japanese theatre: from shamanistic ritual to contemporary pluralism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Randl, Chad. Revolving architecture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008. Print.

Sachs, Edwin. Modern Theatre Stages. New York: Engineering, 1897. Print.

Vermette, Margaret. The Musical World of Boublil and Schönberg: The Creators of Les Misérables, Miss Saigon, Martin *Guerre, and The Pirate Queen. New York: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2006.

Williams, Simon. Shakespeare on the German stage: 1586–1914. Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

WPG, . The Revolving Stage at the Munich Royal Residential and Court Theatre. New York: American Architect and Architecture, 1896. Print.

It also seems that more would be available if I was able to do additional research in German.

Sunday, March 9, 2014

Women in Theatre

I was browsing through Scene Design in American Theatre from 1915 to 1960 by Orville Kurth Larson and something caught my eye – a woman technical director. The author names Carolyn Hancock as the Theatre Guild’s technical director. It also notes that she married Less Simonson.

The book has a variety of other interesting points (I am sure there are many more that I am skipping in my brief browsing of the book:

•In 1924 the scenic artist union starting requiring designers to become a member. This requirement doesn’t seem to prevent crossover between building the productions and designing them (or even directing them).

•The book introduces Cleon Throckmorton, as engineer from the Carnegie Institute for Technology and as a technical director. It also refers to him as a designer including him in the thongs that came to New York and joined the union. In 1930, he opened a commercial shop, and as a way of advertisement sent out the Catalog of the Theatre which is described as “a historical and technical manual of the stagecraft of that period.”

•The author calls out a studio called Wits and Fingers Scenic Studio “formed” by Peter Larson. From references within books, and the age of the union, I think that commercial shops predate scene shops (therefore TD’s) in standalone theatres, but I have little research to prove this theory.

The book has a variety of other interesting points (I am sure there are many more that I am skipping in my brief browsing of the book:

•In 1924 the scenic artist union starting requiring designers to become a member. This requirement doesn’t seem to prevent crossover between building the productions and designing them (or even directing them).

•The book introduces Cleon Throckmorton, as engineer from the Carnegie Institute for Technology and as a technical director. It also refers to him as a designer including him in the thongs that came to New York and joined the union. In 1930, he opened a commercial shop, and as a way of advertisement sent out the Catalog of the Theatre which is described as “a historical and technical manual of the stagecraft of that period.”

•The author calls out a studio called Wits and Fingers Scenic Studio “formed” by Peter Larson. From references within books, and the age of the union, I think that commercial shops predate scene shops (therefore TD’s) in standalone theatres, but I have little research to prove this theory.

Friday, March 7, 2014

Iphone case with tools

Task Lab has an Iphone case that includes 22 tools, basically creating a scenario that looks like a leatherman or gerber turned cell phone case. The case is made from aluminum and polycarbonate, suggesting that it would be strong. Its unique and potentially handy (and sure beats having your screen broken from the tool in your pocket), i'm not sure that I would want to include my phone in some of the situations that my gerber gets used in.

Thursday, March 6, 2014

Claude Hagen- TD, Continued

Upon a little more exploration I was able to find out more about Claude Hagen. Robert Grau wrote about him in The Business Man in the Amusement World, even including a photo of him. Grau calls him the “greastest exponent of the technical side of the stage living at this time.” He discusses his life as well. Hagen was born in Chicago on January 21, 1863. He seemed to get his start (or at least became known about his mechanical ability) in Kansas City in the 1880’s. He was reported to work with Robert Cutler a machinist and technician. He built the Gillis Opera house and stayed as the Master Carpenter. This opera house was apparently just a few blocks away from the Grand Opera House that we visited when we were in grad school which had rigging materials that had survived.

Hagen left the Gillis Opera House to work on the Warder Grand Opera House. Dr. Felicia Harrison Londre in her book about Kansas City Theatre talks about Claude Hagen installing traps and mechanical devices in the space, allowing that it kept him “so busy that he could spare no time to build scenery for the opening.” (The Enchanted Years of the Stage: Kansas City at the Crossroads of American Theatre, 1870-1930)

Grau goes on to say that Hagen toured with combinations as “the foremost stage machinist of his time”, landing at the Fifth avenue Theatre in New York on 1898. He evidently opened up a studio to build scenery, patenting effects, and then in 1900 executed the effects for Ben Hur, and traveled with the show for several years. The stint of the Luna Theatres “Fighting of the Flames” was in 1903, followed by the New Theatre in 1908. The author then claims that the space within the book is too limited to describe the rest of Hagen’s career.

Grau, however, does work with Hagen once more in The Stage in the Twentieth Century: Third Volume, where Hagen describes the New Theatre stage and includes drawings. The book also, much later, mentions that Hagen’s rigging “inventions” are built and distributed by JR Clancy.

It is interesting how much cross over there is between film and theatre. While on one hand this should not be surprising, on the other, today they is not as much cross over as one would think. Yet, it seems novel today how much video is used onstage, and how movie like some shows attempt to be (Dirty Dancing for instance). While some of this influence is that some stage productions as of late are being created on the basis of successful films, it is interesting that the interest in moving scenery in a fluent, film like method has been around over the course of the last century, and really isn’t a very new idea at all.

It would seem from some of Hagen’s writing referred to above, and his chapter on “The Intimate Theatre Idea” published in Architecture and Building vol. XLV published in 1913 that his later career evolved into writing, as I have not found much else about his life after his tenure at the New Theatre. According to the 1940 census, he was living in New York at the Hotel Flanders and he was divorced.

Hagen left the Gillis Opera House to work on the Warder Grand Opera House. Dr. Felicia Harrison Londre in her book about Kansas City Theatre talks about Claude Hagen installing traps and mechanical devices in the space, allowing that it kept him “so busy that he could spare no time to build scenery for the opening.” (The Enchanted Years of the Stage: Kansas City at the Crossroads of American Theatre, 1870-1930)

Grau goes on to say that Hagen toured with combinations as “the foremost stage machinist of his time”, landing at the Fifth avenue Theatre in New York on 1898. He evidently opened up a studio to build scenery, patenting effects, and then in 1900 executed the effects for Ben Hur, and traveled with the show for several years. The stint of the Luna Theatres “Fighting of the Flames” was in 1903, followed by the New Theatre in 1908. The author then claims that the space within the book is too limited to describe the rest of Hagen’s career.

Grau, however, does work with Hagen once more in The Stage in the Twentieth Century: Third Volume, where Hagen describes the New Theatre stage and includes drawings. The book also, much later, mentions that Hagen’s rigging “inventions” are built and distributed by JR Clancy.

It is interesting how much cross over there is between film and theatre. While on one hand this should not be surprising, on the other, today they is not as much cross over as one would think. Yet, it seems novel today how much video is used onstage, and how movie like some shows attempt to be (Dirty Dancing for instance). While some of this influence is that some stage productions as of late are being created on the basis of successful films, it is interesting that the interest in moving scenery in a fluent, film like method has been around over the course of the last century, and really isn’t a very new idea at all.

It would seem from some of Hagen’s writing referred to above, and his chapter on “The Intimate Theatre Idea” published in Architecture and Building vol. XLV published in 1913 that his later career evolved into writing, as I have not found much else about his life after his tenure at the New Theatre. According to the 1940 census, he was living in New York at the Hotel Flanders and he was divorced.

Wednesday, March 5, 2014

Claude Hagen, Technical Director

I came across a New York Times article published on February 11, 1910 that Claude Hagen has tendered his resignation for his position of Technical Director at the New Theatre. He left to establish a “fire show” which he is credited for inventing.

Looking a little further, I found that he was the IATSE International President in 1895-1896.

In the book The New Theatre New York (available for free on google play) lists Claude as the TD under Executive Staff. The book seems as though it was written as part of the founding of the theatre, describing their purpose to be a stock company. The book talks about the German influence, which is interested as some of the other research I have done suggests that the title of Technical Director may have been developed in Germany first. The stage was 100’ wide (between fly-galleries), 119’ to the grid and had a 32’ deep pit. The book credits Hagen for development of stage machinery for the theatre, including a turntable, “sinks” and “bridges”, as well as rigging improvements.

The Green Book Magazine Volume 6 in The Two Years of the New Theatre by Johnson Briscoe states that the opening ceremonies of the New Theatre was on November 6, 1909. Perhaps this is an indicated that the 1906 reference in the above book can be attributed to the start of the company.

Theatre in the United States: Volume 1 expands the description of the stage, saying that the machinery alone cost $250,000 and that it “revolves, moves backward and forwards, or transversely and up and down, as a whole or in parts. It also permits sections of the transverse stage to be dropped, and the rest of the sections to be opened so as to form sinks or cuts through which to lower whole sections.”

Play Production in America, as part of its section on scene shifting devices also mentions the theatre and Hagen, this time in reference to a rigging apparatus that allows ceiling pieces to be placed and moved in coordination with the turntable. This is mentioned in a brief article called Scene Shifting Devices on a website called Old and Sold.

The New York Architect, Volume 3 also discusses the New Theatre and its stage mechanisms.

JR Clancy has a PDF about their company and the history of rigging. John R Clancy started as a stagehand in Syracuse, NY. A show arrived in town, and the theatre’s current rigging system could not handle the shows requirements. Clancy set to work and changed the way that scenery was moved throughout the country. Clancy started to work with Claude Hagen, who is credited with being the TD at both the New Theatre and the Fifth Avenue Theatre. It implies that this relationship predates the New Theatre’s opening of 1906. The Iroquois Theatre Fire of 1903 moved the pair to start working on asbestos curtains and rigging for the curtain to be automatically released.

The American Architect {and} the Architectural Review Volume 122, Part 2 also mentions Hagen as developing a piece of rigging equipment that was able to automatically adjust the counterweight needed for a load (p455). His designs are further supported by patents (these are a few among many):

US1002839

US1045398

US653997

US1063970

The Kid of Coney Island: Fred Thompsan and the Rise of American Amusements also mentions Claude Hagen, crediting him for doing stage effects for a chariot race in Ben Hur, directing Fire and Flames in 1903 for Luna Park, and was connected to Thompson as he was hired to design a stage for the Hippodrome. This would have occurred concurrently to his work at the New Theatre as the Hippdrome opened in 1905.

A New York Times article from 1908 mentions that in Dreamland, Hagen has a “Fire Exhibition”, calling Hagen an owner or the Surf Avenue Fire Show.

Hagen’s work with Ben Hur Is referenced in an article called Filmed Scenery on the Live Stage by Gwendolyn Waltz. This actually referenced an earlier article that appeared within Scientific American that described the effect in detail. Steam at Harper's Ferry talks about the article as well (which I don't currently have access to, which describes the way the race scene was executed. Of not in the blog entry is that Hagen is reported to be from a firm called McDonald & Hagen.

Dr. Felicia Hardison Londre in The Enchanted Years of the Stage: Kansas City at the Crossroads of American Theatre, 1870-1930, also mentions Claude Hagen. Occurring in 1887, this predates the work mentioned above. In this case he was working on a tour (I assume he was traveling with the company) with Edwin Booth and Lawrence Barret. In the scenario mentioned Hagan was working with Augustus Thomas (playwright) when a stagehand let a flat fall during a strike. It isn’t clear from the entry what Hagen’s role was.

I also found a piece written by Claude Hagen, an introduction to The Theatre of Science: A volume of Progress and Achievement in the Motion Picture Industry by Robert Grau. What he wrote though does not elaborate on his own contributions to the entertainment industry.

While this is certainly not a complete history, it is an interesting introduction to an early American TD.

Looking a little further, I found that he was the IATSE International President in 1895-1896.

In the book The New Theatre New York (available for free on google play) lists Claude as the TD under Executive Staff. The book seems as though it was written as part of the founding of the theatre, describing their purpose to be a stock company. The book talks about the German influence, which is interested as some of the other research I have done suggests that the title of Technical Director may have been developed in Germany first. The stage was 100’ wide (between fly-galleries), 119’ to the grid and had a 32’ deep pit. The book credits Hagen for development of stage machinery for the theatre, including a turntable, “sinks” and “bridges”, as well as rigging improvements.

The Green Book Magazine Volume 6 in The Two Years of the New Theatre by Johnson Briscoe states that the opening ceremonies of the New Theatre was on November 6, 1909. Perhaps this is an indicated that the 1906 reference in the above book can be attributed to the start of the company.

Theatre in the United States: Volume 1 expands the description of the stage, saying that the machinery alone cost $250,000 and that it “revolves, moves backward and forwards, or transversely and up and down, as a whole or in parts. It also permits sections of the transverse stage to be dropped, and the rest of the sections to be opened so as to form sinks or cuts through which to lower whole sections.”

Play Production in America, as part of its section on scene shifting devices also mentions the theatre and Hagen, this time in reference to a rigging apparatus that allows ceiling pieces to be placed and moved in coordination with the turntable. This is mentioned in a brief article called Scene Shifting Devices on a website called Old and Sold.

The New York Architect, Volume 3 also discusses the New Theatre and its stage mechanisms.

JR Clancy has a PDF about their company and the history of rigging. John R Clancy started as a stagehand in Syracuse, NY. A show arrived in town, and the theatre’s current rigging system could not handle the shows requirements. Clancy set to work and changed the way that scenery was moved throughout the country. Clancy started to work with Claude Hagen, who is credited with being the TD at both the New Theatre and the Fifth Avenue Theatre. It implies that this relationship predates the New Theatre’s opening of 1906. The Iroquois Theatre Fire of 1903 moved the pair to start working on asbestos curtains and rigging for the curtain to be automatically released.

The American Architect {and} the Architectural Review Volume 122, Part 2 also mentions Hagen as developing a piece of rigging equipment that was able to automatically adjust the counterweight needed for a load (p455). His designs are further supported by patents (these are a few among many):

US1002839

US1045398

US653997

US1063970

The Kid of Coney Island: Fred Thompsan and the Rise of American Amusements also mentions Claude Hagen, crediting him for doing stage effects for a chariot race in Ben Hur, directing Fire and Flames in 1903 for Luna Park, and was connected to Thompson as he was hired to design a stage for the Hippodrome. This would have occurred concurrently to his work at the New Theatre as the Hippdrome opened in 1905.

A New York Times article from 1908 mentions that in Dreamland, Hagen has a “Fire Exhibition”, calling Hagen an owner or the Surf Avenue Fire Show.

Hagen’s work with Ben Hur Is referenced in an article called Filmed Scenery on the Live Stage by Gwendolyn Waltz. This actually referenced an earlier article that appeared within Scientific American that described the effect in detail. Steam at Harper's Ferry talks about the article as well (which I don't currently have access to, which describes the way the race scene was executed. Of not in the blog entry is that Hagen is reported to be from a firm called McDonald & Hagen.

Dr. Felicia Hardison Londre in The Enchanted Years of the Stage: Kansas City at the Crossroads of American Theatre, 1870-1930, also mentions Claude Hagen. Occurring in 1887, this predates the work mentioned above. In this case he was working on a tour (I assume he was traveling with the company) with Edwin Booth and Lawrence Barret. In the scenario mentioned Hagan was working with Augustus Thomas (playwright) when a stagehand let a flat fall during a strike. It isn’t clear from the entry what Hagen’s role was.

I also found a piece written by Claude Hagen, an introduction to The Theatre of Science: A volume of Progress and Achievement in the Motion Picture Industry by Robert Grau. What he wrote though does not elaborate on his own contributions to the entertainment industry.

While this is certainly not a complete history, it is an interesting introduction to an early American TD.

Tuesday, March 4, 2014

Internet Book Archive

Looking around for some information I ran across this Internet Archive. It has many historical theatre books available as a PDF for download.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)